TODAY IS THE DAY I am to gird my loins and rescue my grandchild Benjy from his dragon mother. I am stiff, bleary eyed and trembling and earplugs cannot silence the cacophony in my head. Instead of feeling fit and ready, the early morning sun swats my fragile eyes, every muscle aches and my ancient bones creak as I lift myself from my rumpled bed. I stumble towards the bathroom, to relieve my bladder and my headache, in that order.

TODAY IS THE DAY I am to gird my loins and rescue my grandchild Benjy from his dragon mother. I am stiff, bleary eyed and trembling and earplugs cannot silence the cacophony in my head. Instead of feeling fit and ready, the early morning sun swats my fragile eyes, every muscle aches and my ancient bones creak as I lift myself from my rumpled bed. I stumble towards the bathroom, to relieve my bladder and my headache, in that order.

I’m exhausted from three weeks and an interminable night arguing: with my daughter, my son, my husband and even my doctor who, with one voice, dole out predictions of fresh disaster.

What started as individual nattering naysayers is now an unwelcome Greek chorus—insistent and foreboding. Were I young and naïve, I’d dismiss them out of hand. But I’m old enough to recognize that my daughter (the administrator) and my son (the lawyer) have navigated the river of life more successfully than I and their advice is well meant and assuredly sound.

Too softhearted for my own good, will I take their advice? Probably not, although it’s still not too late to change lanes.

The self-help books that proliferate like rabbits and promise answers to all of life’s puzzles have been of no help. They insist, as in days of yore poets did more eloquently, that you are the master (mistress) of your own fate. Today I find my life’s circumstances so poignant and my fellow players so unpredictable I cannot figure how to create one of those inspiring win-win scenarios. On the Benjy issue, I bob up and down like one of those perpetual motion birds without, so far, having managed to get a sip from the pail on the downward swing.

My daughter Sally, whom I have turned to in later years for comfort and advice, was the first one to whom I confided my concerns about my stepdaughter’s newborn, Benjy. The poor mite was born to a mother who prefers to spend her afternoons lining up for advertisement auditions than worrying about her son’s diaper rash. Like me, Sally has an acid tongue and her response on seeing the photo of Benjy’s small pale face, was harsh.

“Brenda should have had an abortion.” When I flinched, she added, “You agreed at the time. She shouldn’t have had the baby if she planned to dump him on you. She’s just like her mother.”

The mother from hell, Tim and I used to call her, although not in front of the kids. She was the specter in the background when I married Tim: single father of a five-year old daughter, Brenda. The mother, Tim’s ex-wife, had left them years earlier for the love of an itinerant actor but Brenda never gave up hope that one day she would return.

Although I read every book I could lay my hands on and followed advice on caring for stepchildren from all available human and electronic sources, I had failed to make Brenda feel like a birthday girl.

I snatched Benjy’s photo from Sally, “Have some compassion for the poor soul!”

“I have compassion for him, it’s the mother—my self-centered stepsister—I’m pissed off with. Look at him. He looks like the little African babies you’ve been worrying about all these years.”

Sally was right; abortion would have been the rational decision but Brenda’s mother (who had appeared on the scene briefly) had insisted her daughter not have one. Sally had been enraged when Brenda followed her mother’s advice, “Why didn’t she stand up to her for once; Catholic principles my ass.”

Once the baby was born said mother had left town to spend the winter with her recent paramour in Florida. “Mom just isn’t into babysitting,” Brenda had apologized. “You’re better at domestic things, Mother Kate.”

Mother Kate, as she insists on calling me, never intended to compete in that area. I love my kids and Brenda when she’s reasonable, but my life’s ambition never focused on the maternal. My passion, which I had hoped to follow on retirement as single-mindedly as a first love, is languages. I studied French, Russian and German in University and worked as a translator. I always wanted to learn Greek and Latin and who knows maybe Mandarin. As odd as my friends found it, on retirement I had launched into Greek.

When I first considered adopting Benjy—like those African grandmothers do—I knew it was imperative to have the t’s crossed and i’s dotted. Brenda is unpredictable and unreliable and I don’t want to be part of a baby tug of war with the local courts playing Solomon. Calling long distance from Saudi Arabia, my son Chris, when apprised of the situation, doled out advice in his lawyer’s voice.

“No matter what legal adoption documents you have, Mom, if in five years or next week, Brenda comes back into the picture and does her dramatic act about pining for Benjy, the judge will rule in her favor.”

For weeks and particularly the previous night, when lesser mortals were sleeping, the voices of my family and friends have been haranguing me to drop the adoption idea.

In response to my concern about Benjy’s health, our family doctor and friend said, “There’s nothing that a few good meals and a bit of love wouldn’t fix.” When I suggested I might raise my grandson and asked if he gave me ten years to do it, he laughed, “Kate I would have given Tim ten years and he died in his sleep. I’m not psychic. I can’t give you ten minutes.”

Last night, even Tim, raised from the dead for the occasion, started after me.

“Kate, what the hell are you doing? After years of complaining three kids were too much work and how you longed to be free of childcare, you’re signing up to be a mother—of a baby—and in your health.”

Sipping my midnight tea, I was grateful he wasn’t there in the flesh to badger me. But absent though he was, Tim followed me from room to room and hovered over my bed, complaining all the while.

Round and round they all wailed, “It’s Brenda’s responsibility,” “You’re too old,” “What about being grandma to my two kids?”

Finally, I vaulted from bed and shouted, “What about Benjy? Four months old, left with neighbors, mother more worried about breaking into films than whether he’s been fed.”

Then startled to hear myself shouting at shadows, I yanked shut the bedroom window. Next thing my next door neighbor would start pounding on my door. I could only imagine her face when she heard the first of the late night yowls if Benjy moved in.

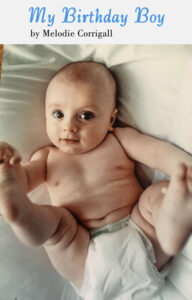

A birthday boy, that’s what I wanted Benjy to be. When I held him and saw his worried face, I just wanted to him to know he was loved unconditionally.

I know that my parents loved me in their way. My father never yelled at me, which was a positive, and on birthdays, my mother added his name to the card. But Dad never noticed what I did until I said I wanted to be a university professor. “No way,” he had said. “Sorry to say, you don’t have the brains for it.” When I settled for being a translator he said, “God knows why you want to learn a lot of foreign languages.” My mother just shrugged from behind his shoulder and smiled apologetically, her focus remaining on her first love.

I had never realized what I missed—as I imagine a sightless person cannot envision the color red—until at university I was in the play Our Town. I played Emily, a young woman who died in childbirth and, being unsettled in death, had the chance to come back to life for one day. She chose her twelfth birthday when she had lived at home with her parents and younger brother. When, as Emily, I came down the stairs, my actress-mother was miming making breakfast, and my brother was being a brother. As Emily, I had cried out, “Look at me, just for a moment, as if I were really here,” and then from the top of the stairs, Emily’s father called out, “Where’s my girl? Where’s my birthday girl?” and the stab of pain that I felt for a father who would call out with such joy was so sharp I almost buckled.

When I told Sally the story to demonstrate how I wanted Benjy to know that he was the world to someone, Sally responded, “We’ll all love him, Mom,” but Sally, herself a “birthday girl,” doesn’t understand.

When I first noticed how fragile Benjy looked, his tiny face pinched and worried, I tried to talk to Brenda about it.

“Oh Mother Kate,” Brenda had said, “They all look like that. They don’t know enough to worry.”

“He’ll learn soon enough,” I had thought.

When I confessed to Sally that I wondered what I should do about Benjy, she jerked to attention.

“What do you mean—do? You always said you weren’t going to be childcare service for your grandchildren and Benjy isn’t even a grandchild.”

“I know but yesterday she left him with that old guy across the hall.”

“So tell her to smarten up.”

“She says she has a chance to get a part and it could be her big break.”

“Ah well,” Sally said escaping to a happier scenario. “You’ll figure something out. I have to put the speed on or I’ll be late picking the kids up at daycare.”

Kisses and promises to take Emily to the puppet show, and I gathered my belongings and went out into the bright day. “Don’t get yourself in too deep,” Sally had called after me.

“Hardly,” I laughed, but the pale little ghost face was slipping in and out of my dreams, calling me.

It’s over thirty years since Chris was a baby, thirty-four since Sally was born, and it all seems like another country. When my first grandchild arrived, I could hardly remember how to change a diaper. I still shiver at the scheduling horror and fatigue of raising three kids, looking after the house for a husband who was often off on business, and managing my own job. I remember feeling like I was standing on quicksand. And now, at sixty-seven, I was thinking of stepping back in. I, who had bored everyone for weeks about how selfish I thought the Italian woman was who became a mother in her sixties.

Still, I had made a commitment and I had been over the to-do list and checked the house many times. It was to be a trial period, as agreed upon by Brenda and me, but I knew that if I took him today, whatever happened, I wouldn’t be able to hand him back.

When the phone rang, I saw it was Sally. Without lifting the receiver, I heard her final warning, “Don’t sign up for more than you can handle,” and it was well-intentioned but I couldn’t face her, I was already too uncertain.

Even then, I could have called Brenda and say I changed my mind. Benjy would never know and Sally would be over the moon. No, I would talk to Sally later and to Chris and even to Tim if he came by again.

As I drove up to the house, two minutes late, Brenda and her boyfriend, Rollie, were waiting by the open door for what Sally would have called the hand-off. I suspect Rollie just wanted to see that his son was really going before he committed to move back in with Brenda.

The three of us, Benjy watching from his car seat, the car packed with more baby gear than I ever could have imagined would be necessary, shuffled out last goodbyes. Seeing Rollie immersed in a cell phone call, I pulled Brenda to the side and whispered, “You’re sure now? Even if the job doesn’t pan out and Rollie heads off, this is what you want?’

I half imagined my stepdaughter, always one for drama, would throw back her head and cry out, “No, you can’t take Benjy, I’m his mother,” but instead she just shuffled her feet and said, “I can’t do it. I can’t be a mom. Now I understand how my mother felt.” Of course she couldn’t, standing there wiggling from foot to foot her eyes on Rollie, who winked back at her.

“I don’t want any changes.” I said, “No games like your mother did. I’m firm about that.”

“Sure Mother Kate, I’ll sign everything at the lawyer’s on Wednesday. When things settle down I’ll set up a regular day to visit Benjy: one day or one afternoon a week when I’ll come by if I’m in town.”

Rollie signaled me to come over to where he was stationed near the door. Holding his hand over the speaker, he sent a kiss and called out, “Thanks Mother Kate,” using a term I only suffer Brenda to use, and I was suddenly rocked by such a wave of rage that I feared I’d rip up the sidewalk on the way to blasting his smug mug.

Instead, I swallowed hard, turned, and climbed into the car. “Best if I don’t come by for a few days,” Brenda said, “Get him used to you and get me some much needed sleep.” Strapped safely into his car seat in the back, Benjy began to snivel.

I secured my seat belt, took a deep breath and backed out the lane, suddenly jarred alert by a speeding car, which veered to avoid me. I struggled to escape around the corner, my hands trembling on the wheel, and tried to control my breathing.

In the special mirror, I could see Benjy’s worried face. He was squeezing the blanket. “We’ll be home soon Benjy,” I called out.

Driving along streets that were so familiar I almost forgot where I was going, ‘what if’s’ began to attack me like a swarm of mosquitoes. What if Sally was right? What if I couldn’t do it? What if the baby didn’t settle in? What if the nanny changed her mind or turned out useless?

What if I fall when I’m carrying him down the front steps?

As always, tension squeezed my gut threatening a bout of diarrhea; my joints seized. I couldn’t avoid the wrinkled old face in the car mirror: no pancake makeup could hide those lines, the slightly caved in cheeks. Five more years and I’d have outlived my own mother.

From the back seat a small mewing sound, rising to a snuffle, and culminating in a wave of sobs. And in the front seat, tears that the baby was still too young to shed were coursing down my face as I joined the chorus: two bawling voices in an unjust world. I wiped my face with my blouse and sat up strong.

“It’s alright, Benjy we’ll be home soon,” I cried out in my cheerful voice, noticing that we were driving past the park where I’d taken the kids thirty years earlier. I stopped the car, noting the No Parking 3-6 sign. “Well it’s only 12:30 now,” I said to comfort us both.

By the time I opened the back car door, Benjy had worked himself up to a good howl. I untangled him, struggling to free the spindly arms out of the straps unharmed. I dug under the seat to find the soother, and plugged it back into his trembling mouth.

I wrapped the tiny body in his new blanket, awkwardly squeezing him to me as I struggled to lock the door; then headed across the park. A smiling dad was talking on his cell phone as he pushed his daughter on the swing.

“Well Benjy,” I said, “What have we got ourselves into?” His sobs seemed to subside and he stared at me. Or maybe not, maybe he couldn’t focus yet, but the movement and closeness had calmed him.

“I think we’ll see a lot of this park,” I said, cheerfully in my ‘it will all work out’ voice. “Little B and I will see a lot of this park.”

Of course, I might not see a lot of it for very many years, as Sally had so bluntly put it. I might not live to see Benjy in school, but what the hell, on the other hand I might live to one hundred and get a card from the Queen of England, who by then would surely be a King. I laughed. Benjy looked startled at the sound. I tried another sound, sort of a gurgle, which seemed to please him.

Who the Hell knew, I thought. Who knew? You could be walking along as healthy as a horse—and who said a horse was healthy—and a piano would fall on your head. So, I would have to be careful not to walk where there might be falling pianos. I started to laugh as I used to with Sally when we would lie on the beach and call to the clouds. Benjy just looked at me and sucked on his soother.

Or maybe I will live happily until I can find the next person to pass Benjy on to, like a precious baton that both runners (anxious and determined) do not want to drop in the race. Maybe I would live long enough so that he would remember how he was Number One to me.

I stared into those small troubled eyes, “How’s my Boy?” I cried lifting him up to the sky, “How’s my birthday boy,” and his mouth twitched as if uncertain whether to cry. I pulled him close to me gathering strength from his small fragile body… “My beautiful birthday boy.”

~ Melodie Corrigall

Published in The MOON Magazine, May 2014

Printed in Stepping in: Raising Our Children March 2019